HP 40gs HP 39gs_40gs_Mastering The Graphing Calculator_English_E_F2224-90010.p - Page 39

Storing and Retrieving Memories, for re-evaluation. Clearly, if the expression is complex

|

UPC - 882780045217

View all HP 40gs manuals

Add to My Manuals

Save this manual to your list of manuals |

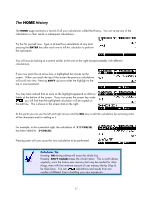

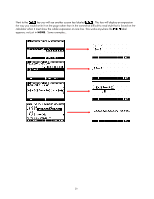

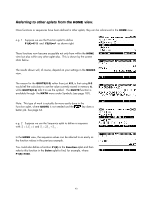

Page 39 highlights

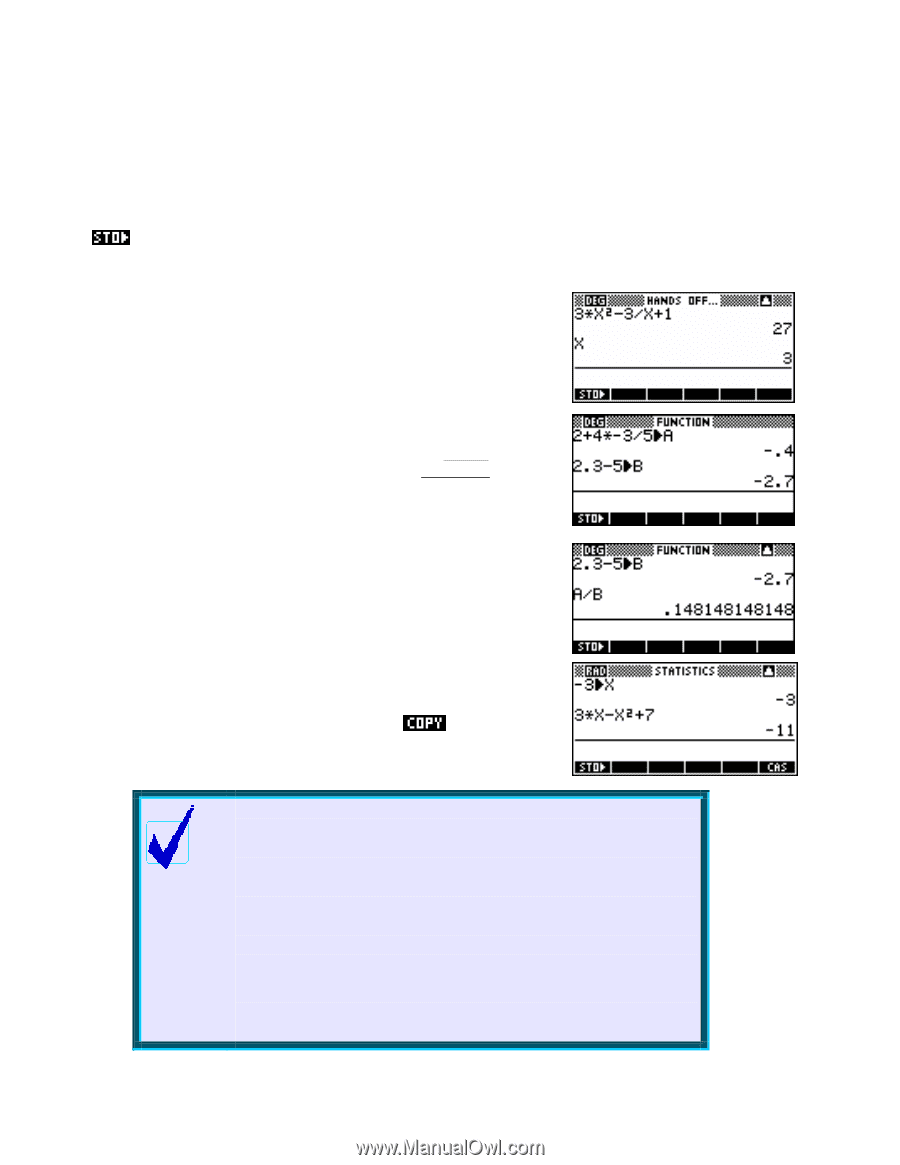

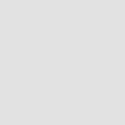

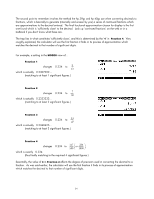

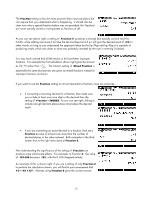

Storing and Retrieving Memories Each of the alphabetic characters shown in orange below the keys can function as a memory. Some examples of this are shown in the third of the four examples above where the values of 1, -3 and -4 are stored into A, B and C prior to the use of the quadratic formula. All of this storing of values is done with the key, which is one of the screen keys listed at the bottom of the HOME view. There are ways of obtaining even more memories than these 26 alphabetic ones, such as storing values into a list (see page 215), but 26 is enough for most purposes. Once stored into memory, values can be used in calculations by typing the letter in place of the value. Typing a letter and pressing ENTER will display memory's contents. See right. There is an advantage to storing results in memories, particularly if they are long decimals, or if you're going to be re-using the result a number of times. 2 + 4 × (−3) As an example, we will perform the calculation of 5 . 2⋅3 − 5 We will do this in two stages, calculating the top and bottom of the fraction and storing the results in memories. Firstly the top of the fraction, storing the result in memory A, then the bottom, storing in B, and then finally the result... As another example, suppose we were evaluating 3x − x2 + 7 for the value x = −3 . We can store -3 into the memory X and then use that symbol in the calculation as shown right. The advantage of this is that if we now wanted to evaluate that expression for other values then we need only store a different value into X and then the expression for re-evaluation. Clearly, if the expression is complex, this can be very helpful. Calculator Tip 1. The memory X is the exception to the above information. It is used to store the current cursor position in the PLOT view so that you can access it in other places. Values stored in X will be overwritten the next time you use the PLOT view. 2. A common error is to forget to put brackets around negatives when evaluating expressions with powers. For example, evaluating x2 − 1 as -32 - 1 rather than as (-3)2 - 1. This can be avoided by storing the value into memory X and evaluating X2-1. This is particularly useful in very complex expressions. Any memory can be used in this way, not just X. 39